Edwina Dumm's Biography

Born July 21, 1893 in Upper Sandusky, Ohio, Edwina Frances Dumm never thought twice about being a woman in the male dominated field of cartooning. In a time when women could not vote, she believed that her talent as an artist was all she needed in order to be successful. Her family encouraged Edwina's sense of independence and permitted her to become a vegetarian at an early age.

Edwina was a little girl who loved to draw. She admired the illustrations for novels such as Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass and Alice in Wonderland, but Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer inspired her more. The troublesome but lovable boy characters in these novels would later influence Edwina's comic strip "Cap Stubbs and Tippie". But for Edwina it was Mark Twain's worldview that affected her more. "You know what Mark Twain said?" she remarked in a 1985 interview. "He said he'd never let school interfere with his education." Mark Twain's idea that personal experience was worth more than formal education stayed with Edwina throughout her high school years. In her senior year, she learned of a new requirement that would force her to take chemistry, a subject she neither liked nor thought necessary for her future. With a group of classmates, Edwina protested the requirement. She was the only student to stand her ground, eventually getting permission to have the requirement waived.

When her family moved to Columbus in 1911, Edwina admitted that she saw no reason to go to high school. "I never wanted to go to school," she recalled. "I swore when I got out of high school that I'd never go in a school as long as I lived."

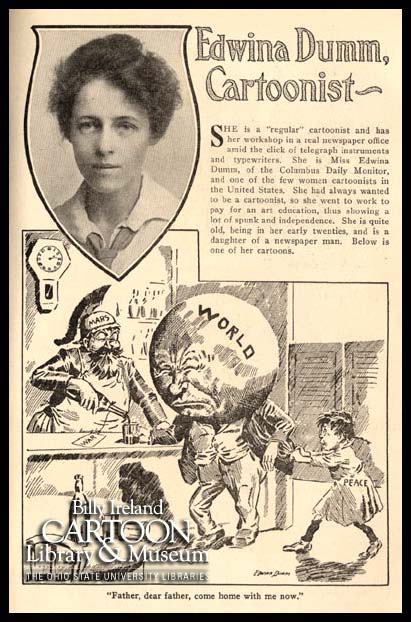

For as long as sketching and drawing had been a staple in Edwina's life, so had pursing her dream of moving to New York City to work as an artist. While her family supported this dream, her father urged her to be sure that she had a back-up plan should a career in art not pay the bills. After graduating from high school, Edwina took a job as a stenographer for the Columbus Board of Education and enrolled in a cartooning correspondence course from the Landon School in Cleveland. Upon completing the course, she applied to be a staff artist at at the Daily Monitor, a new weekly newspaper. She was hired, and began drawing spot illustrations, portraits of politicians and an editorial cartoon. Her work was first published on August 7, 1915. Her first signed cartoon appeared November 27, 1915.

The Monitor began daily publication in July 1916 and Edwina began drawing a daily editorial cartoon at that time. She was the first woman in the nation to work as an editorial cartoonist for a daily newspaper. Recalling her time on the Monitor, Edwina said,. "I thought you had to know a lot about the politics of the past... [but] all you had to know at that time--and possibly today--was what was going on that day and the policy of the paper."

Relying at first on her father for political information, Edwina was soon on her own after he suffered a stroke. Edwina adapted quickly and produced cartoons dealing with issues such as the Mexican War, World War I, prohibition, the economy, and women's suffrage. She drew on the experiences of her friends, some of whom were in the military during the time of the Mexican War, and her own personal viewpoints, such as her views on women's suffrage. Artistic and witty, her cartoons were published for two years until the Monitor ceased in 1917.

Edwina's time at the Daily Monitor gave her enough experience and savings to fulfill her dream of moving to New York City. She immediately went to see George Matthew Adams, a newspaper columnist and founder of the Adams Syndication Service. She had sent him copies of a comic strip that she had created for the "Spotlight Sketches" humor page of the Monitor. "The Meanderings of Minnie" focused on a girl and her dog. Adams liked her work and offered her a contract to draw a comic strip that would run six days a week (no Sunday pages) for his syndicate. Edwina changed her character from a girl to a boy, and her new creation "Cap Stubbs and Tippie" premiered in 1918. A Sunday page was added in 1934.

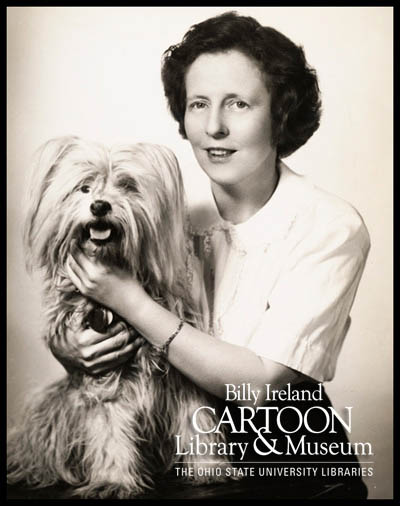

"Cap Stubbs and Tippie" followed the adventures of a mischievous little boy and his shaggy dog. Continuing for almost half a century, the strip amused audiences with its humor and warmth. The lovable pooch and his family inspired several related works, including short stories written by Edwina and sheet music by her New York City roommate Helen Thomas, which Edwina illustrated. Edwina's love for dogs made its way into many of her other works as well, such as "Sinbad" and "Alec the Great," both published during the run of "Cap Stubbs." "Sinbad," named after a reader contest, was published in Life magazine and the London-based Tatler, and later reprinted in Sinbad: A Dog's Life, in 1930. "Alec the Great," which was syndicated from 1931 to 1969, was a single panel cartoon of a dog accompanied by short verses written by her brother, Robert Dumm. These were reprinted in Alec the Great: 1,001 Verses Wise, Witty and Cheerful in 1946.

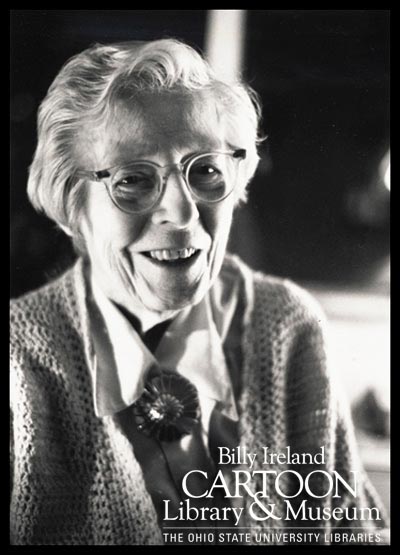

Edwina's success in New York City expanded well beyond her comic strips. She illustrated several books, such as Two Gentlemen and a Lady by Alexander Woolcott and Burges Johnson's Sonnets from the Pekinese. She achieved her dream of creating a cover for Life magazine in 1930 when she illustrated the cover for its January issue. Edwina's achievements were honored in 1978, when she received the Gold Key Award from the National Cartoonists Society Hall of Fame, making her the only woman to receive this honor.

Throughout her life and well into her retirement, Edwina's love for sketching and drawing continued beyond her published cartoons. She produced a variety of drawings and paintings, most of which were done while traveling on the subway in New York City. Her self titled "subway sketches," while never formally published, demonstrate the depth of her artistic talent in her realistic watercolors of people, animals, and crowds, and remain today to be some of her finest pieces of work. Created simply for her own amusement, these works of art clearly show a side of Edwina that wasn't seen in her cartoons and comic strips.

After dedicating more than fifty years of her life to creating cartoon art, Edwina Dumm retired from cartooning in 1966 at the age of seventy-three. She died in New York City on April 28, 1990.

Back to top ^_____________________________________________